FAA & EASA Special Flight Authorizations Differences in Approach and Documentation

19 January 2026

| By Just Aviation TeamBusiness aircraft occasionally need permission to fly when they lack a valid airworthiness certificate or are outside normal certification. In the US, the FAA issues a Special Flight Permit (often called a “ferry permit”) under 14 CFR §21.197. In Europe, EASA (and national aviation authorities) issue a Permit to Fly (PtF) under EASA Part 21 (Subpart P). Both allow an aircraft that is not fully airworthy to fly safely under strict conditions. These insights explain how each system works, and how business jet operators can prepare for these ferry flights.

What Are Special Flight Permits / Permits to Fly?

FAA guidance defines a Special Flight Permit (SFP) as authorization “for any U.S.-registered aircraft that may not currently meet applicable airworthiness requirements but is capable of safe flight”. Common reasons include flying to a maintenance base or storage, delivering/exporting the aircraft, production flight-testing, evacuation from danger, or customer demonstration of a new jet. (The FAA even allows a one-time overweight flight for extra fuel beyond normal range.) The FAA issues the permit on FAA Form 8130-7 (a special airworthiness certificate) with operating limitations.

Likewise, EASA defines a Permit to Fly (PtF) as a special airworthiness certificate granted by derogation from a full Certificate of Airworthiness. It’s used when an EU-registered aircraft “does not meet, or has not been shown to meet, applicable airworthiness requirements but is capable of safe flight under defined conditions”. EASA PtFs cover many of the same situations: production test flights, ferry flights after maintenance, deliveries and exports, customer demonstration, and other non-standard operations.

For example, the regulations explicitly include flights to a maintenance base or storage, ferrying an overweight (for extra fuel) aircraft, and crew training flights by the design/production organisation. Thus, both systems aim to balance safety and flexibility: allowing an aircraft to fly when strictly necessary, under controlled conditions.

FAA Special Flight Permit: Process & Documentation

Under FAA rules (14 CFR §21.197), any U.S.-registered business jet that lacks a current Certificate of Airworthiness may obtain an SFP only for defined purposes (e.g. ferry to repair, export, testing). To request a permit, the operator (or agent) contacts the local FAA Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) responsible for the flight’s origin. The key steps typically include:

Pre-flight inspection and log entry

Before application, the aircraft must be inspected. An FAA-certified A&P mechanic or repair station should certify in the logbook that the jet “is in a safe condition for the proposed flight.” This “safe to ferry” entry is crucial. (Without it, the FAA may send an inspector to examine the aircraft, delaying approval.)

Application (FAA Form 8130-6)

The operator submits an application via the FAA’s Airworthiness Certification portal or on paper using FAA Form 8130-6. Required information includes the aircraft’s registration, type, and serial; a description of why it’s not airworthy; the exact purpose and route of the proposed flight; crew details; and requested operating limitations.

FAA review and issuance

The FSDO reviews the submission (including compliance with any outstanding Airworthiness Directives). If satisfied, it issues FAA Form 8130-7 (Special Airworthiness Certificate – Ferry) along with a one-page operating limitations sheet. Limitations are typically strict: day/VFR flight only (unless otherwise approved), minimal crew and no passengers except essential personnel, and no flight over congested areas unless explicitly authorized. Both the certificate and limitations must be carried on the aircraft.

Obtaining an SFP is often routine if the paperwork is complete and the jet is mechanically sound. For example, if a midsize business jet’s annual inspection has lapsed at a remote airfield, the operator arranges an A&P inspection and logbook endorsement. The operator then applies for an SFP at the nearest FSDO (or through a Designated Airworthiness Representative) with the planned ferry route. Once granted, the jet may fly directly to its maintenance base under VFR, following the FAA’s prescribed limitations.

EASA Permit to Fly: Process & Documentation

In the EASA system, a Permit to Fly is issued by the Member State of registry (or its designated authority), not by EASA itself. Many EU member states’ Civil Aviation Authorities (CAA) have online forms or procedures. A Permit to Fly is typically used in two scenarios for business jets:

(1) a temporary PtF when a jet cannot meet its Certificate of Airworthiness (CofA) requirements (e.g. after an import, major repair, or overdue inspection), and

(2) less commonly, a permanent PtF for ex-military or experimental types (but business jets usually hold full CofAs when possible). The general process is:

Flight Conditions approval

First, one must propose Flight Conditions (FC). These are the restrictions/limitations under which the jet can safely fly. Conditions can include route segments, weather minima, weight limits, equipment checks, test profiles, etc. Typically, an approved maintenance organization or design organization (or the CAA) will review the aircraft’s status and design, and issue a formal approval of the flight conditions (often on EASA Form 18B, which the EASA Agency may co-sign if the issue is safety-of-design). This step ensures the jet is physically capable and ready.

Permit application (Form 20)

With the flight conditions approved, the operator applies for the PtF to the national authority (some countries call it Form 20, others have their own form). The application package includes: proof of registry, the approved flight conditions, aircraft documentation (e.g. weight & balance, maintenance logs, AD compliance), and often a maintenance release (EASA Form 1) or logbook endorsement certifying that the aircraft is safe to fly under those conditions.

Issuance of Permit

The authority (or approved organization) issues the Permit to Fly. In Europe it is a certificate (sometimes laminated card or letter) valid for a specific period or flight(s), listing the conditions (e.g. day/VMC only, minimum equipment, no passengers, etc). Unlike the FAA’s one-time ferry permit, an EASA PtF can cover multiple flights if needed (for example, a series of test flights), until it expires or the aircraft can get a new CofA.

- Example: A large business jet like Global 8000 arrives at a European MRO for heavy maintenance that will take several weeks. Under EASA, the aircraft’s CofA would expire once it left the airworthiness review cycle. The operator coordinates with an EASA-approved Part-145 organization which performs the maintenance and signs off on the work with an EASA Form 1. The Part-145 or the CAA defines flight conditions (for example, limit to final check flight to runway only). The national CAA then issues a PtF allowing the repositioning of flights under those conditions. The operator then flies the jet off the ramp and to its destination as authorized.

Key Differences in Approach

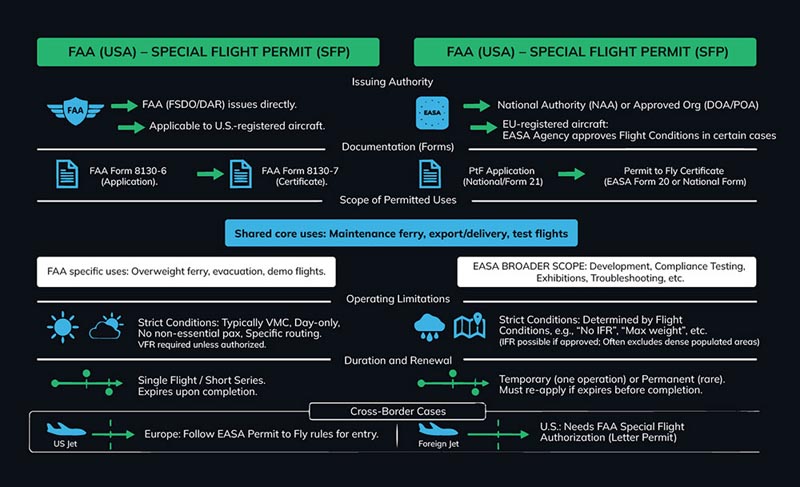

While FAA Special Flight Permits and EASA Permits to Fly serve similar purposes, they differ in authority, documentation and scope:

Issuing Authority

FAA SFPs are issued directly by the FAA (via FSDO or a DAR) for U.S.-registered jets. By contrast, EASA PtFs are issued by the national authority where the aircraft is registered (or by a privileged Design or Production org). EASA’s central Agency (EASA) only approves the Flight Conditions in certain cases (safety-of-design issues); otherwise, the NAA handles the entire process.

Form 8130 vs Form 20

In the US, the official paperwork involves FAA Form 8130‑6 (application) and the resulting 8130‑7 certificate. In Europe, operators use a national PtF application (often based on the EASA-approved Form 21) and the authority issues a Permit to Fly certificate (sometimes modeled on EASA Form 20 or national forms). A design organization with PtF privileges may even issue a PtF using EASA Form 20B under its Design Organization Approval (DOA), provided it obtains prior FC approval.

Scope of Permitted Uses

The lists of allowable flights are largely similar but phrased differently. Both allow ferry for maintenance, export/delivery, and test flights. FAA lists core purposes in 14 CFR §21.197 (ferry to maintenance, delivery/export, production flight test, evacuation, demo flights, plus overweight ferry). EASA’s list (Reg. 2019/897 21.A.701) covers all that and more: development flights, compliance testing, crew training for flight testing, customer acceptance, exhibitions, troubleshooting flights, etc. (For business operators, the key overlaps are ferrying for maintenance or storage, overweight fuel flights, and export/delivery.)

Operating Limitations

Both systems impose strict conditions. Under FAA SFP, limitations usually confine the flight to VMC, day-only, no non-essential passengers, and specific routing. EASA PtFs similarly include conditions like “only IFR flight plan not permitted” or “max weight” etc as determined by the flight conditions. One notable point: U.S. ferry permits often explicitly require VFR (unless special IFR authorization is given), whereas EASA may allow IFR ferry if the approved Flight Conditions permit it. Also, in Europe the standard PtF may exclude flights over densely populated areas unless waived (some CAAs are relaxing this for certain Part-21 aircraft).

Duration and Renewal

An FAA SFP is typically for a single ferry flight or a short series of flights and expires upon completion. An EASA PtF can be temporary (for one operation) or can be a permanent permit (rare for business jets). If the PtF expires before the jet can continue (for example, if additional positioning is needed), it must be re-applied or revalidated. In practice, both regimes expect the aircraft to re-enter normal airworthiness (or storage) promptly.

Cross-border cases

Business operators often move aircraft internationally. A U.S. business jet exported to Europe must follow EASA PtF rules for entry, and vice versa. Additionally, a foreign-registered jet flying to the U.S. needs an FAA Special Flight Authorization. The FAA defines this as a letter permit on official letterhead for a non-U.S. plane without a U.S. CoA. For example, if a Swiss-registered jet wants to fly into the U.S. on a one-time basis without full FAA certification, it would need the FAA’s special flight authorization (and possibly Department of Transportation approval) before filing a U.S. flight plan.

Documentation and Preparation

For business operators, the key is preparation of paperwork and ensuring technical compliance. Official sources emphasize the following:

- Aircraft Records: Log all maintenance accurately. Before an FAA SFP or EASA PtF, a mechanic must certify the aircraft’s status. In the U.S., this means making a logbook entry per 14 CFR 43.9, indicating the jet is “safe for ferry flight.” In Europe, an EASA Form 1 (Certificate of Release to Service) is needed for any maintenance. Having these documents ready shows the regulator that the jet can indeed fly safely under the permit.

- Application Forms: Use the correct forms. In the U.S., the FAA’s online Airworthiness Certification (AWC) tool or FAA Form 8130-6 is used. For EASA/PtF, national CAA websites often provide an “Application for Permit to Fly” or accept the EASA Form 21-based application. Include aircraft registration evidence (e.g. N-number or nationality certificate) and any bilaterals for imports/exports.

- Flight Plan and Itinerary: Regulators expect a detailed route. Include all fuel stops, alternates, and comply with any navigation requirements. (For example, some PtFs forbid Unmanned Air System (UAS) or require specific ATC permission segments.) Always coordinate with the authorities in advance.

- Insurance and Crew Qualifications: The flight is typically still covered by your normal insurance, but check that the policy covers ferry flights under permit. Crew must hold valid licenses and medicals, as usual; however, note that passengers (beyond essential crew or inspectors) are usually not allowed on a special flight permit.

- Regulatory Notifications: In Europe, some authorities require notification of a PtF issuance (especially temporary ones) and may inspect the aircraft at origin or destination. The FAA generally does not inspect at destination, but the permit must remain valid until the aircraft lands and the next maintenance action begins.

FAQs

1. Can a Special Flight Permit or Permit to Fly be used for revenue-generating flights?

No. Both FAA Special Flight Permits and EASA Permits to Fly strictly prohibit commercial or revenue operations. Flights are limited to the approved purpose only (e.g., repositioning, testing, delivery), regardless of the operator’s AOC or commercial status.

2. Does a Permit to Fly replace an Airworthiness Review Certificate (ARC) under EASA?

No. A Permit to Fly is not a substitute for an ARC. It is a temporary authorization allowing flight outside normal airworthiness. Once the aircraft returns to compliance, a new ARC and full Certificate of Airworthiness are required.

3. Are Minimum Equipment Lists (MELs) applicable during Special Flight Permit or Permit to Fly operations?

Generally no. Minimum Equipment Lists apply to fully airworthy aircraft. Under FAA and EASA permits, aircraft are operated under explicit flight conditions, which override MEL logic and define exactly what systems must be operative for that specific flight.

4. Can international overflight permissions be affected by a Permit to Fly?

Yes. Some states require advance notification or may impose restrictions on aircraft operating under special permits. Operators must verify acceptance of FAA or EASA-issued permits with each overflown state, even when operating purely non-commercially.

5. Who holds legal responsibility for compliance during a permitted flight?

The aircraft operator retains full responsibility. Approval of a Special Flight Permit or Permit to Fly does not transfer liability to the authority. Operators must ensure compliance with all stated limitations, documentation carriage, and operational conditions throughout the flight.

6. Can a Permit to Fly or Special Flight Permit be amended after issuance?

Yes, but not informally. Any change to route, purpose, weight, or operating conditions requires re-approval by the issuing authority. Verbal coordination without updated documentation is not considered valid regulatory authorization.

7. Is cabin configuration or interior status relevant to permit approval?

Yes. Missing or modified interior components can affect weight and balance, emergency equipment compliance, and evacuation assumptions. Authorities may require updated weight-and-balance data or restrict occupancy even if the flight is non-passenger and non-commercial.

8. How do authorities verify continued compliance during multi-leg permit flights?

Through documentation checks and potential ramp inspections. For EASA PtFs, authorities may limit validity to specific dates or legs. FAA permits typically terminate upon completion of the authorized flight sequence, regardless of remaining calendar validity.

Navigating FAA and EASA special flight authorizations requires more than regulatory awareness; it demands operational foresight, precise important documentation, and timing. For business jet operators managing cross-border movements, understanding these differences reduces delays, costs, and compliance risk. This is where experienced operational support matters. With a strong focus on business aviation workflows, Just Aviation helps operators translate regulatory requirements into smooth, executable flight operations worldwide.

Sources

- https://www.faa.gov/media/29886

- https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/14/21.197

- https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/domains/aircraft-products/permit-fly

- https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/document-library/easy-access-rules/online-publications/easy-access-rules-initial-airworthiness-and?page=2&kw=307

- https://www.faa.gov/aircraft/air_cert/aw_cert/special_flight_authorization