ICAO Doc 8168 PANS OPS and Its Effect on Business Jet Performance in Complex Airspace

09 February 2026

| By Just Aviation TeamThe importance of understanding ICAO Doc 8168 PANS-OPS has grown significantly for business flight operators navigating increasingly complex global airspace. These procedure design standards directly influence airport accessibility, performance planning, and operational flexibility for business jets. A clear operational perspective on PANS-OPS enables more accurate dispatch decisions, reduced risk exposure, and improved predictability across international business aviation operations.

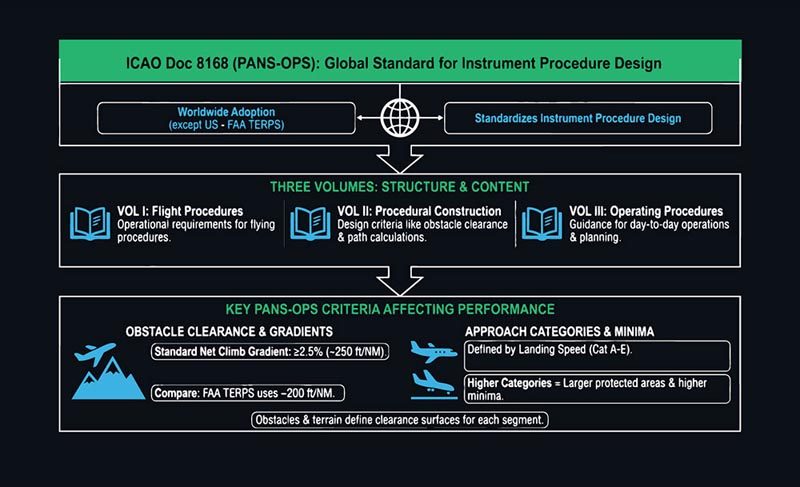

ICAO Doc 8168 (PANS-OPS): Global Standard for Instrument Procedure Design

ICAO Document 8168, commonly referred to as PANS-OPS (Procedures for Air Navigation Services – Aircraft Operations), establishes the worldwide standard for designing instrument flight procedures, including departures, arrivals, approaches, and missed approaches. It is adopted by civil aviation authorities globally, except in the United States, where the FAA uses Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS).

PANS-OPS is structured into three volumes:

- Volume I – Flight Procedures: Defines the operational requirements for flying instrument procedures.

- Volume II – Procedural Construction: Provides detailed design criteria, including obstacle clearance standards and lateral/vertical path calculations.

- Volume III – Operating Procedures: Guidance for day-to-day operational application and flight planning considerations.

Procedures developed under PANS-OPS assume all-engines-operating conditions, as highlighted by the FAA: “operators are responsible for planning contingencies, such as single-engine or abnormal operations.”

Key PANS-OPS Criteria Affecting Performance

PANS-OPS design specifies obstacle clearance and path constraints that directly impact aircraft performance. For example, climb/descent gradients and approach speeds are standardized. In PANS-OPS the net climb gradient from runway or missed approach must be at least 2.5% (approximately 250 feet per NM). (By comparison, FAA TERPS uses about 200 ft/NM as a standard gradient.) Any PANS-OPS departure or missed-approach segment that requires more than 3.3% climb will have that higher gradient explicitly published on the chart.

Obstacles and terrain define these gradients; PANS-OPS includes detailed obstacle-clearance surfaces for each segment of an instrument procedure. Similarly, approach procedures are classified by approach category (speed). ICAO defines Categories A–E by landing speed. Business jets at fast approach speeds typically fall into Category C (121–140 kt) or even D (141–165 kt). Higher categories mean larger protected areas, higher minimum visibility and higher circling altitudes. For example, PANS-OPS circling minima for Cat C and D are 394 feet of obstacle clearance, reflecting conservative buffers. In practice, this means a heavy jet in Cat D will face more restrictive minima than a smaller turboprop.

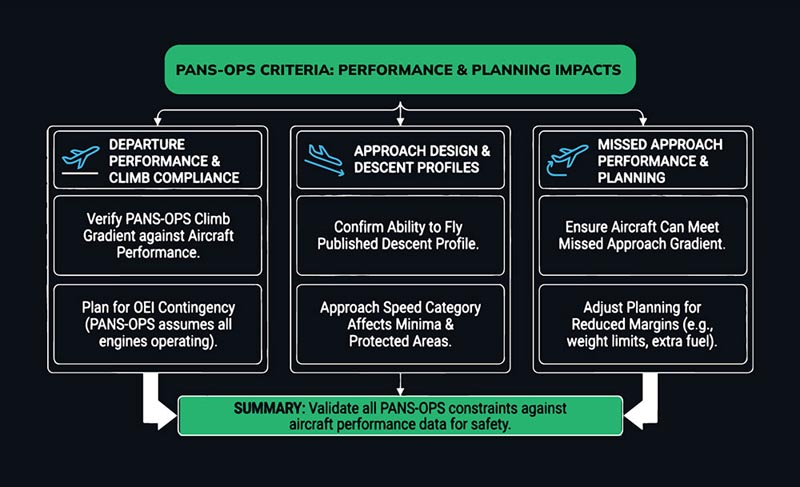

Operational Implications for Business Jet Performance and Planning

Instrument departures designed under PANS-OPS frequently include explicit minimum climb gradients to ensure obstacle clearance within the protected area. While the baseline assumption is all-engines-operating performance, the operator bears full responsibility for confirming that the aircraft can achieve the published gradient at the planned takeoff mass, atmospheric conditions, and runway configuration.

Departure Performance and Climb Gradient Compliance

For business jet operators, PANS-OPS criteria translate into direct performance and planning requirements, with climb capability typically being the first limiting factor. When a published SID or obstacle departure procedure specifies a minimum climb gradient (such as 2.5% or higher) the aircraft must be capable of achieving that gradient at the planned takeoff weight. Operators are therefore required to compare the published PANS-OPS gradient against aircraft flight manual (AFM) or flight management system (FMS) climb performance data.

For example, if a departure procedure requires a 3.3% climb gradient (330 ft/NM) to ensure obstacle clearance, a heavy long-range business jet may need to reduce takeoff weight or limit fuel uplift to remain compliant. As PANS-OPS procedures are developed assuming normal, all-engines-operating performance, operators must also account for abnormal scenarios. In practice, this often leads to the development of internal one-engine-inoperative (OEI) departure strategies or the application of conservative takeoff weight limits to maintain adequate safety margins.

Approach Design, Descent Profiles, and Speed Categories

On the arrival side, PANS-OPS design directly influences approach geometry and operational minima. Approaches with vertical guidance, such as ILS or APV procedures, are typically based on a nominal 3° glide path. However, local obstacle environments may result in steeper final descent angles. For non-precision or LNAV/VNAV procedures, charts may publish descent gradients in ft/NM, requiring careful verification during flight planning.

Business jet operators must confirm that the aircraft can fly the published descent profile while maintaining stabilized approach criteria, particularly when operating at higher landing weights. Aircraft approach speed category further affects applicability and minima. Many business jets fall into ICAO Category C, which entails larger protected areas and higher visibility requirements than Category B. As a result, Category C aircraft may face higher landing minima or restrictions on circling procedures, especially in terrain-constrained environments.

Missed Approach Performance and Operational Planning

Missed approach procedures designed under PANS-OPS assume a minimum climb gradient of 2.5%, again based on normal aircraft performance. When executing a go-around, the aircraft must be capable of meeting this gradient at the expected configuration, weight, and environmental conditions. If climb margins are reduced (for example, during high-temperature or near-maximum-weight operations) operators must plan accordingly.

This planning may include briefing alternate missed approach strategies, selecting runways with less restrictive climb requirements, or adjusting landing weight targets. From a dispatch perspective, these considerations can also influence fuel planning, such as carrying additional contingency or alternate fuel to accommodate slower climb profiles or extended level-offs. Ultimately, each PANS-OPS-imposed constraint (whether related to climb gradient, descent profile, speed category, or turn altitude) must be validated against aircraft performance data, with operational adjustments made as necessary to ensure compliance and safety.

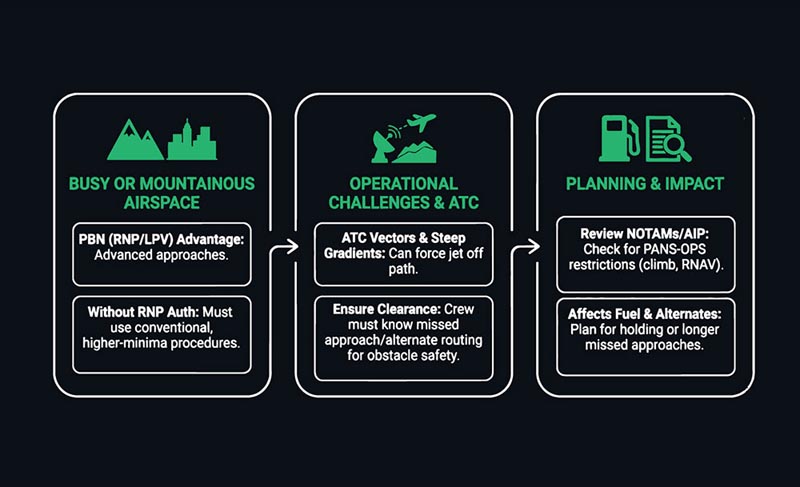

Complex Airspace and PANS-OPS Considerations

In busy or mountainous airspace, PANS-OPS effects can be magnified. Complex airspace often relies on RNAV (RNP) arrivals and departures with many altitude/track constraints. Business jets equipped for Performance-Based Navigation (PBN) (e.g. RNP‑AR or LPV) can take advantage of advanced approach procedures designed with PANS-OPS criteria.

However, if the jet lacks the required RNP authorization, the operator must avoid those approaches or use higher-minima conventional ones. Also, vectoring and ATC interventions in dense airspace may force a jet off the published path. Operators should therefore ensure crews understand any missed approach or alternate routing (which may be based on PANS-OPS criteria) to maintain obstacle clearance.

For example, high-altitude or mountainous airports often have SID procedures with steep turns and climb gradients to avoid terrain. Likewise, congested airports may have multiple crossing Standard Instrument Departure (SID)s or Standard Terminal Arrival Route (STAR)s that quickly escalate the required altitude. If ATC vectors a business jet early, the operator must still ensure a safe gradient on the new path.

In practical terms, dispatchers often review NOTAMs and AIP notes for any PANS-OPS restrictions (climb gradients, altitude limits, Area Navigation (RNAV) requirements) in complex airspace. These can affect fuel planning (extra fuel for holding or longer missed approaches) and operational decisions like alternate selection.

Steep Mountain Departure

Consider a large business jet departing an alpine airport where PANS-OPS requires a 3.3% climb to 5,000 ft within 5 NM. If the jet is near MTOW, its AFM data may show it cannot achieve 3.3% on a single-engine climb. The operator might then reduce takeoff weight, carry extra fuel (to alternate if the jet must hold longer), or use a flatter climb SID (if available) and accept a longer ground roll. This illustrates how an obstacle-rich environment under PANS-OPS can force payload or fuel trade-offs.

High-Speed Approach

A business jet flying Cat C into a coastal airport may face higher weather minimums and a tight final segment. PANS-OPS might publish a LNAV/VNAV approach with a 2.5% missed climb and a final descent angle of 3.5°.

During dispatch, the operator notes the required climb rate and descent angle. If winds are strong or the jet is heavy, the crew may brief reduced flaps or speed on final to ensure they can climb out if missed. The high category speed also means a larger circle-protected area; if circling is required, minima might be quite high, so the operator ensures an alternate airport is chosen accordingly.

Complex RNAV Arrival

In very busy airspace, PBN STARs and Required Navigation Performance – Authorization Required (RNP-AR) approaches (designed per PANS-OPS Vol II) may have many altitude step-down fixes. A business jet with full FMS and Performance-Based Navigation (RNP) certification can fly these closely, but one without Barometric Vertical Navigation (BARO-VNAV) or Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) might have to use an alternate procedure.

For dispatch, this means checking the PANS-OPS-based arrival for altitude/temperature limits. For instance, a very cold temperature limit on a BARO-VNAV approach (per PANS-OPS guidance) could disqualify that approach for the day, requiring an ILS or higher minima procedure instead. Operators must catch these constraints in advance and plan diversions or extra fuel as needed.

FAQs

1. How does PANS-OPS influence airport suitability assessments for business jets?

PANS-OPS criteria directly affect declared gradients, approach minima, and turn protection. Operators must assess whether an airport’s published procedures align with their aircraft’s certified performance, especially when evaluating alternate airports or seasonal operational feasibility.

2. Does PANS-OPS affect payload planning beyond takeoff performance?

Yes. PANS-OPS constraints can indirectly limit payload by driving fuel requirements for missed approaches, longer routings, or higher alternates. These factors may reduce available payload even when runway length alone appears sufficient.

3. How should operators interpret published climb gradients in PANS-OPS procedures?

Published gradients represent minimum obstacle clearance under normal operations. Operators should compare these with aircraft performance margins, not just minimum compliance, to account for temperature, runway condition, and operational variability during dispatch planning.

4. Why do some PANS-OPS approaches restrict temperature or barometric settings?

Certain PANS-OPS procedures rely on barometric vertical guidance. Temperature limitations ensure altitude accuracy. When limits are exceeded, operators may need to prohibit use of the procedure or apply corrections, affecting arrival planning and alternate selection.

5. How does PANS-OPS impact long-range business jet route efficiency?

PANS-OPS-designed arrivals and departures may impose altitude or track constraints that reduce optimal climb or descent profiles. This can increase fuel burn and time, requiring operators to adjust cost calculations for specific destinations.

6. What role does aircraft approach category play in PANS-OPS compliance?

Approach category determines obstacle clearance areas, visibility minima, and circling limits. Faster business jets often fall into higher categories, which can restrict access to certain procedures or increase landing minima, influencing airport and timing decisions.

7. Can PANS-OPS affect operational reliability during peak traffic periods?

Yes. In complex airspace, PANS-OPS procedures often include tight sequencing and altitude windows. Any deviation or delay can cascade into holding or re-routing, making schedule reliability more sensitive to procedural constraints.

8. How should operators integrate PANS-OPS into risk management processes?

Operators should incorporate PANS-OPS constraints into pre-flight risk assessments, reviewing gradients, temperature limits, navigation requirements, and alternates. This supports informed go/no-go decisions and reduces exposure to last-minute operational disruptions.

Understanding how ICAO Doc 8168 PANS-OPS shapes procedure design allows business flight operators to make informed decisions on airport selection, fleet utilization, and risk management. When these criteria are properly integrated into dispatch and planning workflows, operational predictability improves. With this perspective, operators working alongside experienced aviation consultancies such as Just Aviation can better align regulatory requirements with performance realities across complex global airspace environments.

Sources

- https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC_120-105B.pdf

- https://www.icao.int/sites/default/files/APAC/APAC-FPP/FPP%20Training/FPP%20Training%20in%202025/PANS-OPS%20Procedure%20Design%20Initial%20Course%202025/Presentations/D12-D13-PA-MAP.pdf

- https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC_120-91A.pdf