Handling Services in the U.S.: Adapting to Regional and FAA Standards

25 January 2026

| By Just Aviation TeamBusiness aviation operators must master a web of domestic and international regulations when planning and handling flights. In the U.S., FAA rules (under 14 CFR Parts 91/135, etc.) govern everything from flight planning to equipment requirements, while individual airports or regions may impose their own procedures (noise curfews, special use airspace, local taxes, etc.). The sections below outline the key permits, navigational requirements, documents and considerations for light, mid, and heavy business jets, comparing domestic (U.S.) flights with international operations.

Business Jet Categories and Certification

Business jets are generally classified as light (e.g. VLJs under ~12,500 lb), mid-size, and heavy jets (typically commercial-sized aircraft). Regardless of size, they must hold a valid U.S. airworthiness certificate and registration, and meet applicable noise and emissions standards (e.g. Stage 3 or 4 noise certification for jets).

Operators follow either Part 91 (private/corporate) or Part 135 (charter) regulations, and some fractional operations use Part 91K.

For foreign-registered jets flying to, from or within the U.S., the operator also needs a DOT-issued permit and FAA Part 129 OpSpecs (Foreign Air Carrier approval). In summary, every business jet must meet FAA airworthiness and certification rules, and operators must ensure their OpsSpecs and insurance cover domestic versus international routes.

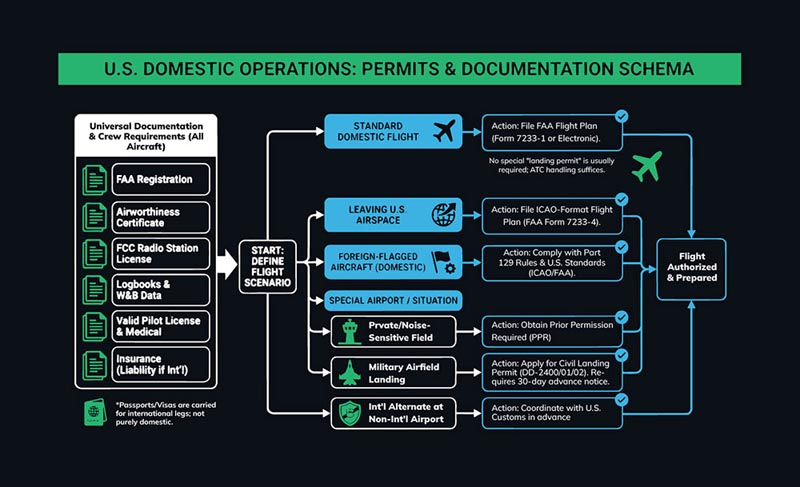

Domestic (U.S.) Operations: Permits and Documentation

Within the U.S., most domestic flights require no special “landing permit.” An FAA flight plan filed with ATC (FAA Flight Service or electronic) suffices. Operators simply file an IFR (or VFR if legal, though jets usually fly IFR) flight plan under FAA Form 7233‑1 or electronic equivalent. (If leaving U.S. airspace, the ICAO-format form (FAA Form 7233‑4) is required.) For foreign-flagged aircraft flying domestically, Part 129 rules apply, and they must comply with U.S. standards (e.g. ICAO Annexes and FAA regulations) once approved.

All aircraft must carry required documents: FAA registration, airworthiness certificate, radio station license (from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)), and any extra logbooks or weight-and-balance data. Each crew member must have a valid pilot license and medical. Insurance must be arranged. In general, domestic flights do not require U.S. customs or immigration pre-clearance, so no CBP form or passport is needed for purely domestic hops. However, crews should always carry passports when leaving the country, and visas if required.

At domestic airports, some facilities impose Prior Permission Required (PPR) procedures for non-scheduled arrivals (common at private or noise-sensitive fields). Likewise, landing at a military airfield (other than Coast Guard) requires a civil landing permit and 30-day advance application using DoD Forms DD-2400/2401/2402. If choosing a non-“international” airport for an international flight’s alternate, operators must coordinate with U.S. Customs in advance. In practice, most business jets use major international airports or well-equipped GA fields to avoid these extra steps.

Domestic Navigation and Equipment Standards

U.S. domestic navigation uses an extensive airway system. Business jets equipped with GNSS (GPS/Wide Area Augmentation System) and RNAV FMS can file direct Area Navigation (RNAV) routes (including T‑routes/Q‑routes) or the legacy Victor/J-route system. No special regional navigation certificate is needed beyond proper equipment approval; FAA now requires ADS-B Out (1090ES or UAT) for flight in Class A/B/C airspace or above 10,000 ft over the contiguous U.S. (ADS-B In is encouraged but not required.) RVSM (Reduced Vertical Separation) is standard above FL290, so jets must be RVSM-certified to use FL290–410 (most business jets are).

In summary, domestic nav follows FAA PBN/RNAV rules: any RNAV 5 (GPS) system is usually sufficient for enroute, and standard ILS/LPV approaches are available at nearly all key airports. Operators ensure altimeters are set to U.S. standard (29.92″ Hg or local QNH) and file domestic ATC routes via Flight Service or dispatch software.

Unlike some countries, the U.S. has few en-route charges for domestic flights (no ATC overflight fees for U.S. carriers within U.S. airspace). Weather briefings, SNOWTAM/NOTAM checks, Temporary Flight Restriction (TFR) notices (e.g. for presidential movements), and fuel stops are part of normal planning. Short-runway or high-altitude airports require performance planning, especially for heavy jets.

Many operators use automated flight-plan filing services or Flight Service Station (FSS) to distribute the flight plan to ATC. All domestic IFR flights must have a current weather briefing, flight plan file time < 1 hour before departure, and normally follow FAA routes (star/DP from FAA charts or ATC-assigned vectoring).

International Operations: Permits, Documentation, Navigation

International flights bring extra compliance steps. Advance Passenger Information (APIS) is mandatory: U.S. Customs and Border Protection requires an electronic manifest of passengers and crew to be submitted (via eAPIS) before departure for or from the U.S. Typically this is done 30–60 minutes before departure (or longer if required). Operators must also file an ICAO-format flight plan (FAA Form 7233‑4) for any flight exiting U.S. domestic airspace.

This plan includes entry of any required permit numbers (overflight or landing permit codes) in Item 18. For many destinations, filing the ICAO flight plan itself covers “advance notification,” but some countries require a separate landing permit application days in advance (handled through local agents). As one FAA guidance notes: “For some countries, a filed flight plan meets [notification], while others may require specific written notification many days before the flight”. In practice, operators often use international trip support services or FBOs to obtain overflight/landing permits and slot clearances in each country en route.

Required Documents

Operators should carry multiple copies of important aircraft documents on international flights. This includes airworthiness and registration certificates, all crew licenses/medicals, radio station and operator permits (FCC documents), insurance certificates, and maintenance logs as needed.

Crew passports (and visas if required) must be valid. U.S. passport holders need a passport for almost all foreign entry and re-entry to the U.S. Weight-and-balance data, fuel load sheets, and equipment lists (e.g. for special equipment) should also be carried. Any special cargo or dangerous goods must comply with ICAO TI and U.S. Hazmat regs.

Customs/Immigration

On arrival outside the U.S., operators follow the destination country’s procedures. For example, flights into Canada must phone the CBSA Telephone Reporting Centre at least 2 hours before arrival (providing flight details, ETA and passenger info). Likewise, flights into the U.S. require filing the CBP electronic APIS passenger manifest and landing at a U.S. port of entry.

When returning to the U.S., the pilot files a general declaration (CBP Form 7507) and crew/passenger (Form 6059B) if returning from international flight. Separate customs decals or pre-approval (e.g. Customs Seal) may be required if operating regularly between the U.S. and certain countries.

Navigation

Outside the U.S., navigation standards follow ICAO PBN rules. IFR flights to Europe or Asia use published airways or Organised Track Systems (e.g. North Atlantic Tracks) and require equipment like HF radio or SATCOM for oceanic segments. An HF radio (or equivalent) is mandatory when beyond VHF coverage; likewise, an altitude-reporting transponder (Mode C/S) is required to cross into or out of U.S. ADIZ airspace.

Some regions (e.g. Europe) mandate redundant nav (e.g. two IFR nav sources) and have speed/altitude/route clearances (e.g. RNP AR approach approvals). Crews must plan routes via foreign Flight Information Regions (FIRs) using the appropriate high-altitude jet tracks or low-altitude networks, and obtain oceanic clearances (position reporting, no-ADS-B zones) per each FIR’s rules.

Key Operational Considerations

Flight Planning

Use ICAO flight plans for any segment leaving the U.S. FIRs. Consult AIPs and Foreign NOTAMs to handle differences (e.g. metric altitude in some areas, local ATC phraseology). Always account for additional fuel for international diversion airports, possible headwinds on oceanic routes, and en-route fees (e.g. Pacific Overflight Fee). File international plans with customs offices timing in mind: some countries expect filing up to 12–48 hours ahead, especially for heavy jets or VIP flights.

Navigation Equipment

Ensure avionics meet all planned airspace mandates. For North Atlantic crossings, for example, a full FANS 1/A or equivalent with Controller–Pilot Data Link Communications (CPDLC) and ADS-C may be needed. Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum (RVSM) approval is required above 29,000 feet almost globally.

Many business jets operate with Inertial Reference System (IRS) and GPS combinations, but foreign air traffic control may require dual IFR navigation, so operators should carry current charts and ensure Multi-Function Displays (MFDs) are fully updated. Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) registration at 406 MHz is now globally mandated; while the United States permits older 121.5 MHz ELTs, international flights should carry a 406 MHz ELT registered with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Communication

Operators should be prepared for the U.S. ATC using English and standard phraseology. In other countries, English is also standard for international flights, but local language may be used on ground or in uncontrolled airspace. HF radios are necessary for transoceanic segments beyond VHF range. Some regions (e.g. Caribbean, Mexico) use the U.S. flight plan system up to entry, then switch to local Flight Plan ICAO formats.

Customs/Security

For U.S. departures and arrivals, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) have specific rules. Security screening of passengers is the operator’s responsibility. U.S.-bound corporate flights must submit Advance Passenger Information System (APIS) data and wait the required 30/60 minutes before departure for CBP processing. Arriving U.S. flights require customs deplaning in sterile areas designated by CBP.

U.S. flights to some countries (for example, certain Middle Eastern or Caribbean islands) may require advance security notice under TSA or host-nation rules. Contraband and agricultural restrictions apply everywhere: for example, the United States prohibits the import of certain meat and produce items, and many countries disallow soil or specific animal products without inspection.

Regional Differences

Note that “regional standards” can also mean variations among countries. For instance, Europe (EASA) now requires all jet flights to carry an EASA Part-NCC (non-commercial) or part-NCO (commercial) compliance document, whereas the U.S. uses FAR Part 91/135.

Canada and Mexico have their own flight rules (CARs and RACR) which generally align with ICAO but have unique currency or training requirements (e.g. a Canadian private pilot license alone is not enough for Canadian charter ops; an FAA certificate or Validation is needed). While deep detail is beyond this scope, operators should always check the national AIP of the country visited for differences from FAA standards (as ICAO AIPs note any variances.

Summary of Documentation & Permits

- Required Onboard: FAA registration & airworthiness, pilot/crew licenses and medicals, FCC radio licenses, noise certificates (if Stage 2), weight/balance, MEL, crew visas/passports. (For foreign ops, local equivalents of these documents.)

- Pre-Flight Filing: ICAO-format IFR flight plan (FAA 7233‑4) for any international leg. CBP eAPIS manifest for US arrivals/departures. Overflight/landing permits per country, often handled via agent (permit numbers go in FP’s remarks).

- Clearances: Oceanic position reports on North Atlantic (NAT) or Pacific tracks. ADS-B equipment checks (on board). PPR at airports with slot controls or noise restrictions. CBP port of entry notification if using a non-international U.S. field.

- Insurance: At least $1–2M liability, often more for international. Some countries (Mexico) require local liability insurance even if U.S.-registered.

By carefully planning each flight according to these FAA and regional rules (using official AIPs, FAA notices, and local guidance) business flight operators can ensure compliance and smooth handling, whether flying cross-country or around the world.

FAQs

1. What is the typical turnaround time for business jets at major U.S. airports?

Turnaround depends on jet size and airport infrastructure. Light jets at Teterboro (TEB) or Van Nuys (VNY) can refuel, deice (in winter), and board passengers in 30–45 minutes. Heavy jets at Miami (MIA) or Dallas Love Field (DAL) may require 60–90 minutes, especially when customs, catering, and ground support services are included.

2. How do Part 91 and Part 135 crew duty regulations differ for operators?

Under Part 91, no specific duty or rest limits exist, though operators often implement corporate policies for safety. Part 135 mandates strict rules: maximum 14-hour duty day, 8-hour minimum rest, and 30-minute rest breaks for flights over 8 hours. For example, a heavy jet flying from New York (JFK) to Los Angeles (LAX) under Part 135 must log crew duty start/end times precisely for FAA compliance.

3. Can business jets operate into airports without published instrument approaches?

Yes, but only under VFR conditions. IFR flights require at least one published FAA approach (e.g., ILS, RNAV/GPS). For example, Aspen/Pitkin County Airport (ASE) has challenging terrain, so IFR operators must file RNAV approaches. Operators may request ATC visual approaches at controlled airports like Teterboro (TEB), but only if weather and traffic conditions permit.

4. How do noise abatement procedures affect departures and planning?

Noise-sensitive airports impose specific departure profiles. For example, Los Angeles (LAX) and San Francisco (SFO) require reduced thrust takeoffs and steeper climb angles to minimize community noise. Operators must calculate performance impacts, brief crew, and include the procedure in preflight planning. Non-compliance can result in fines or restricted slot access.

5. What electronic filing options are available for domestic and international flight plans?

FAA flight plans can be filed via Flight Service, EFBs, or approved dispatch software. Domestic IFR flights typically use FAA Form 7233‑1; international departures require ICAO flight plan format (FAA Form 7233‑4). Equipment codes must reflect RNAV/ADS-B status, e.g., a Gulfstream G550 using RNP 1 capabilities must indicate RNAV/RNP compliance for ATC.

6. Are there performance considerations for high-altitude or short-runway airports?

Yes. Airports above 5,000 ft MSL, such as Denver (DEN) or Telluride (TEX), require careful density altitude calculations. Operators must adjust takeoff thrust, reduce payload, or plan longer runway usage. Heavy jets like the Bombardier Global 7500 require precise fuel and passenger planning at high-altitude airports to maintain climb gradient and obstacle clearance.

7. How are Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFRs) communicated to business operators?

FAA issues TFRs via NOTAMs and the official TFR website. Operators must review TFRs before dispatch, including presidential movements, wildfire zones, and space launches. For instance, a TFR at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) may restrict aircraft within 30 nm; operators must file alternate routing to avoid violations and ensure ATC coordination.

8. What special procedures apply for international flights returning to the U.S.?

International arrivals must submit electronic APIS manifests to CBP prior to departure. For example, a flight from London Heathrow (EGLL) to New York JFK must submit passenger and crew data 30–60 minutes before departure. Arrival is only allowed at U.S. ports of entry with customs facilities; alternate airports require prior coordination. Operators should also verify insurance coverage for international operations if flying through regions like the Middle East.

9. How do airport-specific handling requirements affect business jet operations?

Requirements vary by airport. At Teterboro (TEB), slot restrictions limit operations to preassigned times; late arrivals require rescheduling. At Aspen (ASE), winter operations necessitate anti-icing/deicing coordination. Miami (MIA) demands customs coordination for international arrivals. Operators must integrate these requirements into dispatch planning, often days in advance.

10. Are there special considerations for VIP, medevac, or charter business flights?

VIP and medevac flights may qualify for expedited handling or PPR exemptions. For example, medevac operations at Phoenix Sky Harbor (PHX) often receive priority ramp access. However, FAA, TSA, and CBP regulations still apply. Operators must coordinate security screening, ground handling, and customs procedures while maintaining full regulatory compliance.

Seamless business jet operations in the U.S. demand meticulous planning, regulatory compliance, and awareness of regional nuances. Just Aviation offers specialized guidance and resources to help operators navigate permits, documentation, and airport-specific procedures efficiently. By integrating expert insights with practical operational tools, operators can optimize flight planning, ensure compliance with FAA and international standards, and maintain smooth, predictable ground handling across all domestic and international destinations.

Sources

- https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/ifim/intl_overview/

- https://www.faa.gov/hazmat/air_carriers/operations/part_129

- https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/fs_html/appendix_a.html

- https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/technology/equipadsb/resources/faq

- https://www.cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/publications/dm-md/d2/d2-5-12-eng.html