Flight Operations Efficiency Across the U.S. and Canada: Key Insights

29 January 2026

| By Just Aviation TeamCross-border U.S.–Canada traffic is a major segment of international business flying (the U.S.–Canada corridor accounts for roughly 11.8% of U.S. international traffic, ~31.5 million passengers in 2024). These insights examine operational factors (route planning, airspace and regulatory rules, and airport handling) that affect efficiency for business jets on both sides of the border, highlighting key differences and best practices in each country.

Route Planning and Airspace Coordination

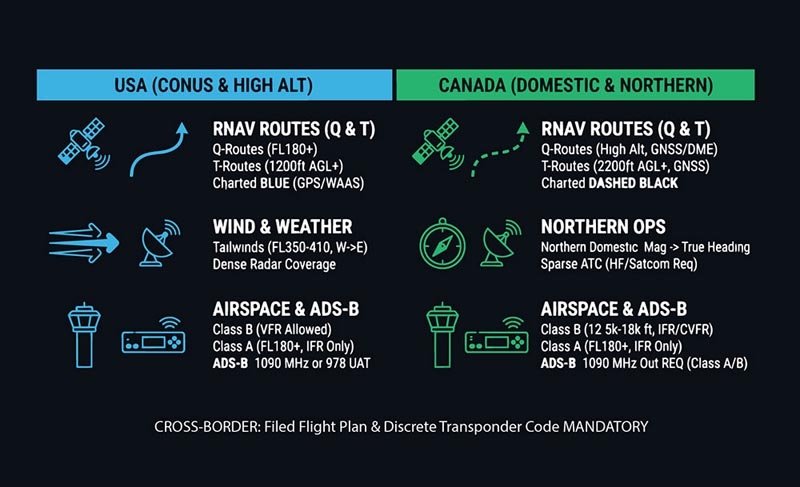

Business jets typically fly on published airway and RNAV routes to maximize speed and fuel efficiency. Both countries use high-altitude “Q” RNAV routes and low-altitude “T” RNAV routes.

RNAV Route Structures in the United States and Canada

In the U.S., Q-routes (FL180 and above) and T-routes (1,200 ft AGL up to FL180) are charted in blue (GPS/WAAS required). Canada’s RNAV network is similar: high-altitude Q-routes (GNSS or DME/DME/IRU navigable) and low-altitude T-routes (from 2,200 ft AGL up, GNSS-required) appear as dashed black lines.

Business jets, equipped with modern FMS/GPS, routinely use these RNAV routes for more direct paths. (Note: Canadian T-routes start a bit higher (2,200 ft) than U.S. ones, reflecting domestic airspace design.)

Wind Patterns, Altitude Strategy, and ATC Coverage Considerations

Wind patterns must also inform route optimization. West-to-east flights in North America often benefit from jet-stream tailwinds, especially at FL350–FL410, whereas east-to-west flights may choose lower altitudes to avoid strong headwinds. In Canada’s far north (Northern Domestic Airspace), operators must be aware that navigation can switch from magnetic to true headings, and radar/ATC coverage is sparse.

In fact, in Canada radar and ATC services are limited to the southern populated corridors; beyond those, operators may need to rely on HF or satellite comms and file position reports. In contrast, the contiguous U.S. has denser radar coverage, but both systems require filing a flight plan when crossing the border. (U.S. regulations require a filed flight plan and discrete transponder code for all flights crossing the U.S.–Canada border.)

Airspace Classification and Surveillance Equipment Requirements

Airspace classification differs between the two countries. In Canada, Class B low-level controlled airspace exists from 12,500 ft up to but not including 18,000 ft, and is restricted to IFR and controlled VFR (CVFR) operations. VFR flights must obtain ATC clearance before entering Canadian Class B, whereas in the U.S. VFR is allowed in Class B (with separation provided). Also, Canadian Class A begins at 18,000 ft (similar to U.S. Class A) and is IFR-only.

Business jets flying high altitudes will, in both countries, need to comply with RVSM and ADS–B mandates. Notably, Canada requires 1090 MHz ADS–B Out for Class A/B flights, whereas the U.S. accepts 978 MHz UAT for lower-altitude flights. Ensuring ADS–B equipment meets Canadian specs is essential when planning in Canadian airspace.

Regulatory and Border Procedures

Cross-border operations involve regulatory clearances and customs processes that can impact scheduling.

Canadian and U.S. Entry, Customs, and Operator Authorization Requirements

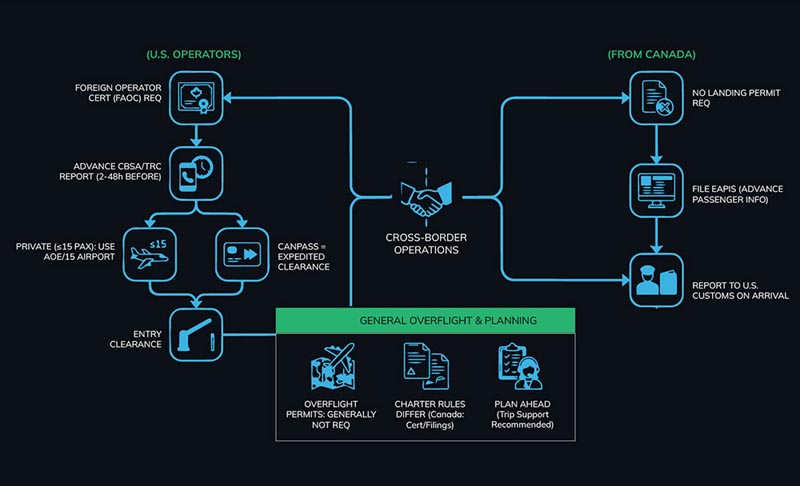

In Canada, foreign operators (including U.S. business aircraft) must hold a Canadian Foreign Air Operator Certificate and, for commercial charters, obtain permission under Canada’s Aviation Regulations. Flights into Canada require advance CBSA notification. Private/business flights (≤15 persons) use an Airport of Entry (AOE/15) and must report to the Canadian Telephone Reporting Centre (TRC) 2–48 hours before arrival.

The CANPASS Private Aircraft program can greatly speed clearance: members may land at any AOE (even outside office hours) and receive expedited processing. Flights into the U.S. do not need a “landing permit,” but must comply with U.S. Customs rules. Aircraft must file Advance Passenger Information (via eAPIS) before U.S. entry, and report to U.S. Customs on arrival. Staying informed on both countries’ entry rules is key (e.g. U.S. eAPIS deadlines and Canada’s AOEs).

Overflight Permissions, Charter Rules, and Operational Planning Considerations

Operators should also note that overflight permits are generally not required between the U.S. and Canada for business aviation, but weight and charter rules differ. For example, Canada requires an operator certificate and certain license filings for foreign-charter flights regardless of weight, whereas a small private U.S. bizjet can fly to Canada as a “non-scheduled” service if paperwork is in order. (Large international carriers follow bilateral aviation agreements and DOT licensing.) In practice, planning the flight plan and customs filings well ahead (ideally with professional trip-support coordination) avoids last-minute delays.

Airport and Ground Operations

Turnaround efficiency at airports is a vital part of operational performance. Business jets generally aim for rapid ground handling: disembark/embark, fuel, catering, etc. simultaneously.

Technology-Driven Turnaround Optimization at North American Airports

Airports (and carriers) are investing in technology to shave minutes off gate times. For instance, Vancouver International Airport (YVR) is deploying an AI-powered “Deep Turnaround” system to monitor and optimize gate processes in real time. (YVR describes turnaround as a “coordinated sequence of ground activities at the gate”; from fueling and baggage to catering and cleaning.) Such innovations highlight that systematic coordination of fueling, de-icing, loading, and catering can significantly improve on-time performance.

Ground Handling Variability, Weather Impacts, and Coordination Practices

Regardless of location, ground service quality varies. In Canada, winter weather can extend handling time due to De/Anti-Icing operations and cold-weather procedures (Transport Canada publishes strict Holdover Time guidelines to ensure safe de-icing). U.S. airports often have more 24/7 FBOs, while some smaller Canadian airports have limited hours; requiring careful scheduling of arrivals/departures.

Efficient operators coordinate their requests to ground handlers and customs brokers in advance. For example, filing passenger and crew information early (US eAPIS 1–4 hours before U.S. departure) and calling the Canadian TRC 2+ hours before Canadian arrival are standard practice. On the ramp, parallel processing (e.g. loading catering while refueling) minimizes delay. In busy hubs, a typical airline turn might be 45–60 minutes, but a light business jet with proactive planning can often turn around in 30 minutes or less.

Parking, Slot Constraints, and Turnaround Planning at Congested Airports

Across both countries, parking and slot restrictions at peak airports can affect timing. Many large U.S. and Canadian airports require advance notice for any turnaround exceeding a set time (often 30–60 minutes) or for parking stands.

Operators should check slot or gate requirements, especially in congested centers like Toronto, New York, or Vancouver. When possible, routing via smaller relief airports or FBOs can avoid delays; for instance, flying into a nearby Canadian airport with U.S. pre-clearance. (Note: as of 2025 some Canadian airports offer U.S. CBP preclearance (meaning cleared for the U.S. before boarding) which can save arrival time.)

Strategic Takeaways

These strategic practices help ensure business aircraft spend more time flying efficiently and less time waiting on the ground:

Leverage RNAV/PBN

File direct GPS/RNAV routes (Q/T routes) when possible. Both U.S. and Canada publish extensive RNAV networks; ensure GPS/WAAS equipment meets RNAV-2 standards. This often yields shorter tracks and fuel savings.

Plan for Airspace Rules

Remember Canadian Class B (12.5–18 kft) is IFR/CVFR only. Secure ATC clearances for any VFR portion in Canadian airspace. Ensure ADS-B ‘Out’ gear meets the 1090 MHz requirement for flights above 10,000 ft in Canada.

Early Clearance Coordination

File flight plans and customs notifications as soon as possible. US-bound flights should submit eAPIS before departure; Canada-bound flights should call the TRC 2+ hours ahead. Consider CANPASS enrollment for repeat Canada trips.

Optimize Ground Ops

Communicate with ground handlers and FBOs in advance. Build overlap between processes (e.g. refueling while passengers board). Take advantage of technology (airport turnaround tools or FBO apps) to track servicing progress. In winter, factor in de-icing procedures and compliance with HOT guidelines.

Use Data and Feedback

Review actual block times vs schedules to identify delays. For example, airports like YVR now use data analytics to pinpoint bottlenecks. Operators can similarly analyze past flights (fuel burn, taxi time, handling time) to refine future plans.

FAQs

1. How do U.S. and Canadian ATC flow-management practices impact business jet scheduling?

The U.S. uses structured traffic flow initiatives during peak periods, while Canada relies more on strategic pre-tactical planning. For operators, this means U.S. delays are often issued closer to departure, whereas Canadian constraints are typically visible earlier during flight planning.

2. Are preferred IFR routings handled differently for business jets in the U.S. and Canada?

Yes. The U.S. frequently publishes preferred and advisory routes that may prioritize traffic density over directness. Canada places greater emphasis on flight-planned efficiency if separation standards are met, often allowing more direct routings for high-performance business aircraft.

3. How do altitude allocation practices differ for business jets crossing the border?

Canada tends to allocate higher initial cruise levels earlier for business jets due to lower enroute congestion outside major corridors. In the U.S., step climbs are more common, particularly near major hubs, impacting fuel planning and time-to-cruise calculations.

4. What operational considerations exist for nighttime business jet arrivals in Canada versus the U.S.?

Canadian airports more frequently impose night staffing limitations for customs, fueling, or handling services. In the U.S., 24-hour operational availability is broader. Operators should verify after-hours service confirmations in Canada to avoid extended ground delays.

5. How does surveillance coverage affect operational planning for business jets in Canada?

Outside southern Canada, reduced radar coverage can lead to increased reliance on procedural separation and position reporting. While transparent to crews, operators should account for slightly longer ATC spacing, which may affect arrival sequencing and block-time accuracy.

6. Do contingency fuel strategies differ between U.S. and Canadian operations?

Yes. Canadian alternates may be spaced farther apart in some regions, requiring more conservative contingency fuel planning. In the U.S., denser airport networks allow tighter alternate strategies, improving payload flexibility for short-notice business missions.

7. How do airport slot philosophies differ between the two countries for business aviation?

U.S. slot controls are more formalized at select congested airports, whereas Canada relies more on airport-level coordination and parking approvals. For business operators, Canadian access is often flexible but requires earlier confirmation for extended stays.

8. Are operational documentation audits approached differently by authorities?

Canadian authorities emphasize pre-arrival document completeness and conformity, while U.S. oversight is more event-driven. Business flight operators benefit from standardized document packages when operating into Canada to reduce administrative friction during ramp or desk reviews.

Operational efficiency across the U.S. and Canada depends on informed planning, precise documentation, and a clear understanding of how regional systems differ for business aviation. With experience supporting complex cross-border missions, Just Aviation focuses on translating regulatory nuance and operational insights into practical execution, helping operators streamline decision-making, reduce friction, and maintain consistent performance across North American business jet operations.

Sources