How To File A Flight Plan Step By Step?

23 November 2024

| By Just Aviation TeamCreating a flight plan is a critical step in ensuring a safe journey. It outlines your intended route, how to file a flight plan, and the steps involved, providing vital information to air traffic services. By creating a flight plan, you communicate essential details like departure, destination, and expected time en route. This process is not just a formality; it’s a safeguard. Should an unexpected event occur, your flight plan is the key to prompt search and rescue operations. Always remember, a well-prepared pilot follows the file a flight plan steps meticulously for every flight.

What is a Flight Plan?

A flight plan is indeed a detailed document that includes a variety of information critical to the safety and efficiency of the flight. In addition to the pilot’s name, aircraft type, departure and arrival points, estimated time en route, and alternate airports in case of an emergency, a flight plan also typically includes:

- Aircraft registration and communication equipment on board.

- Route of flight, including any airways or fixes to be used.

- Cruising altitude or flight level.

- Fuel on board and fuel consumption rate, to calculate the range of the aircraft.

- Number of passengers on board, if any.

- Emergency equipment available on the aircraft.

- Pilot’s contact information and license number.

Effective flight planning is essential for business aviation safety and regulatory compliance. Pilots and operators must gather all critical information (route, weather, aircraft, crew, and alternate aerodromes) before filing. The FAA’s Aeronautical Information Manual emphasizes that “prior to every flight, pilots should gather all information vital to the nature of the flight, assess whether the flight would be safe, and then file a flight plan”.

A well‐prepared flight plan not only outlines your intended route, altitudes, and timing, but also provides vital data to air traffic control (ATC) and search‐and‐rescue services in case of an emergency. In short, careful planning helps ensure safe, efficient flight operations and regulatory compliance.

Types of Flight Plans

Business jet operators should understand the main flight plan categories: IFR, VFR, Composite, DVFR, and International (ICAO) flight plans.

IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) Flight Plans

These are used for flights under instrument conditions (IMC) or when operating in controlled airspace by instrument clearance. All IFR flights must file an IFR flight plan. In fact, ICAO Annex 2 and the FAA AIM both mandate a filed flight plan for any IFR operation.

The FAA’s official “Air Traffic by the Numbers” report for FY2023 recorded approximately 15.71 million IFR flights and 14.07 million VFR flights, underscoring the scale of operations relying on standardized planning. An IFR plan specifies the exact route (often via airways or ATC-assigned tracks), cruising altitude or level, and other details (performance capabilities, equipment) needed to obtain ATC clearance and separation.

VFR (Visual Flight Rules) Flight Plans

These plans are for flights conducted in Visual Meteorological Conditions (VMC) under visual navigation. VFR flight plans are not always required, but they are strongly recommended whenever the flight will operate cross‐country, in busy airspace, or outside simple traffic areas. A filed VFR plan allows ATC to provide flight following and triggers search‐and‐rescue if the aircraft is overdue.

For example, many operators file a VFR plan when departing a controlled airport or flying through Class C/B airspace. (Note that ICAO Annex 2 still requires flight plans for VFR flights departing/arriving controlled zones or crossing FIR/UIR boundaries.) VFR plans include departure, route (visual checkpoints or airways), estimated times, pilot info, and ensure ATC is aware of the flight.

Composite Flight Plans

These combine IFR and VFR segments in a single itinerary. A composite plan (also called “mixed IFR/VFR”) is used when a flight will operate under VFR for one portion and under IFR for another. It is mostly used in special operations (e.g. some military or survey flights) and requires careful coordination: the IFR portions follow instrument procedures, while the VFR portions use visual navigation. For most civil business flights, operators simply file separate VFR or IFR plans instead of a composite plan.

DVFR (Defense VFR) Flight Plans

A DVFR plan is filed by a VFR aircraft operating in an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) or similar national-security area. In DVFR airspace, the aircraft must be easily identifiable for defense purposes. In practice, a DVFR flight plan is very much like a VFR plan but includes extra military-related information (e.g. ADIZ entry point and time). U.S. and Canadian ADIZ rules require DVFR plans when approaching their coastlines. The pilot must also report to ATC before crossing the ADIZ boundary. DVFR plans “ensure that ready identification, location, and control of aircraft are maintained in the interest of national security”.

International (ICAO) Flight Plans

Any flight entering international airspace must use the ICAO flight plan format (usually based on ICAO Doc 4444) to ensure interoperability across countries. Maximizing business jet flight planning and schedule management, this standardized structure allows authorities to accurately interpret key details such as route segments, equipment codes, and alternates. In the U.S., for example, the FAA accepts all IFR, VFR, and DVFR plans in the international (ICAO) format using FAA Form 7233-4. Operators flying internationally should use the ICAO format so that national air traffic services can process the flight plan without conversion.

Is Filing a VFR Flight Plan Necessary for Cross-Country Flights?

For both scheduled and non-scheduled business flights, filing a VFR (Visual Flight Rules) flight plan for cross-country flights is not a regulatory requirement, but it is highly recommended for safety reasons. The primary purpose of a VFR flight plan is to provide a means for search and rescue (SAR) to locate an aircraft in case of an emergency. For example, a VFR flight plan would typically include the aircraft’s departure point, destination, route, estimated time en route (ETE), and information about the pilot and passengers.

This information is crucial for SAR operations if the aircraft becomes overdue or is reported missing. While not mandatory, the benefits of filing a VFR flight plan include increased safety and the facilitation of efficient use of airspace. It is particularly important when flying through remote areas or over water, where the likelihood of visual detection by others is reduced. In controlled airspace, such as Class B or C, or when entering an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ), specific requirements may necessitate filing a flight plan.

Flight Plan Components

A comprehensive flight plan contains key elements that must be planned and documented carefully:

Navigation and Route Planning

The route is the core of the flight plan. Pilots should select appropriate airways, jet routes or direct segments, taking published SIDs, STARs, and oceanic tracks into account. Altitudes are chosen based on aircraft performance, direction of flight (odd/even flight levels), and ATC restrictions. The FAA advises that “the route of flight [must be] accurately and completely described… file via airways or jet routes established for use at the altitude or flight level planned”. In practice, you spell out each airway or fix and transition point. For example:

- “DPL V16 TOLER L603 SEA” (via Victor 16 to TOLER intersection, then Victor 603 to Seattle).

- When flying off-airways (radial-to-radial), list the navaids/fixes in sequence.

Accurate route definition simplifies ATC clearance. Always check Aeronautical Information Publications (AIPs) or enroute charts for the latest route structures and airway availability.

Fuel Planning

Fuel calculations must cover the entire mission with reserves. For IFR flight in the U.S., 14 CFR 91.167 requires enough fuel to fly to the destination, then to an alternate (if one is required), plus 45 minutes of cruise fuel at normal cruise (30 min for helicopters).

Business jets flying long flights typically carry still more: planned fuel, final reserve, contingency fuel (for wind or routing changes), and extra fuel if conditions are marginal. Operators should consult ICAO Annex 6 and regional regulations for fuel policies, but at minimum ensure compliance with 91.167. A detailed fuel plan includes fuel on board, burn rate, alternates, and final reserves to guarantee safety even with unexpected delays or diversions.

Permit Requirements

International flights often require overflight and landing permits for each country. Flight planning should include checking permit requirements and lead times. For example, certain nations demand visa/permit for foreign-registered jets or passengers.

If a route traverses special use or restricted areas (e.g. parts of Siberia or the Middle East, except the restricted ones named above), operators must verify permissions or re-route around prohibited airspace. Similarly, diplomatic clearance is needed when flying VIP charters. Good practice is to start permit applications well before departure (often 24–72 hours in advance), or to file a route that avoids sensitive airspace if permits are uncertain.

Crew Requirements and Responsibilities

The flight plan must reflect the crew complement and qualifications. For a business jet this usually means a qualified PIC (pilot in command) and, if required by regulation or company policy, a second-in-command. Crew duty-time rules (FAR Part 121/135 or EASA OPS 1 rules) dictate rest periods and maximum duty.

The PIC is ultimately responsible for the plan’s accuracy and safety. Crew responsibilities include ensuring all licensing, medical, and competency requirements are met for the flight (e.g. IFR currency, type ratings, language proficiency), confirming the briefing data, and completing all preflight checklists. In some countries, crew names may be submitted with the flight plan or passenger manifest, so have that information ready.

Aircraft Data and Emergency Equipment

The plan must identify the aircraft (registration/N-number, type designator) and its performance category (e.g. “M” for business jet with wake turbulence). Equipment codes must reflect the onboard navigation, communication, surveillance, and approach capabilities (for example, “S” for standard transponder, “G” for GNSS, “W” for RVSM, etc.). FAA Form 7233‑4 Item 10/18 and ICAO Annex 2 require listing all instruments and datalinks (GPS, DME, CPDLC, etc.)

Also include any emergency or survival gear: for instance, life rafts or ELTs if flying long over water or polar routes. This information ensures ATC knows what procedures (like RNP approaches) the aircraft can fly, and that rescue agencies have clues (e.g. life raft count) if needed.

How To File A Flight Plan?

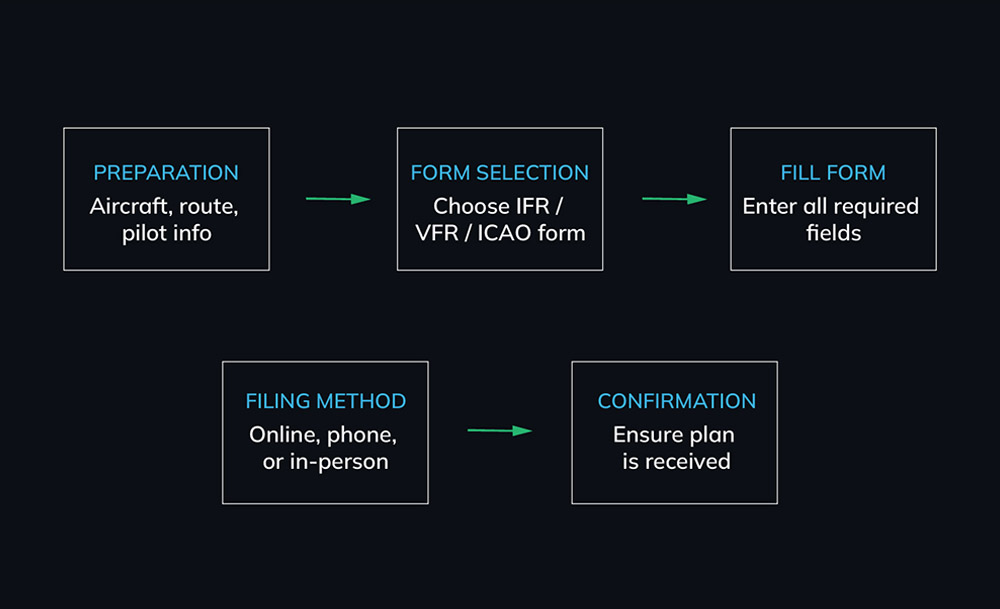

Filing a flight plan involves several steps, backed by ICAO, FAA, and EASA guidance:

1. Pre-filing Preparation

Before submitting, self-brief on all relevant factors. Obtain weather reports/forecasts (METARs, TAFs, SIGMETs), notice of adverse conditions (e.g. thunderstorms, icing), NOTAMs for route aerodromes and navaids, and any airline/operator dispatch notes. Review NOTAMs and the latest AIPs for route changes or special procedures. Confirm runway conditions and any airport restrictions (curfews, runway closures). Operators should gather all information (aircraft weight, equipment, alternate options, crew readiness) and “assess whether the flight would be safe” before filing.

2. Complete the Flight Plan Form

Use the proper flight plan format. In the U.S., most flights are filed on the FAA Form 7233-4 (International Flight Plan). This single ICAO-formatted sheet covers both domestic and international routes. (Only certain flights (e.g. USAF/DoD or domestic “stereo routes”) use the older FAA Form 7233-1.) International flights and high-altitude requests always use 7233-4. Online filing tools or FSS prompts will guide you through each ICAO item (items 7–19, including route, ETE, alternates, etc.).

Be precise: list the departure ICAO code, route (with airways and fixes), destination code, requested altitude, etc. Fill in aircraft ID, type, category, and equipment exactly. If capabilities like RVSM or CPDLC are available, include the appropriate PBN/ and COM/ entries in the “Other Information” field. Re-check the form for typos or omissions (especially the route segment, which is a frequent source of errors).

3. Submit the Flight Plan

Once filled, submit the plan to an official filing agency. In the U.S., file with a Flight Service Station (FSS) either by phone, radio (before departure), or electronic means. Many operators now use approved flight-planning websites or company dispatch systems which relay plans to ATC.

In Europe and elsewhere, flight plans go via AFTN/AMHS to the national AIS or Eurocontrol’s NM (IFPS) system. If calling a Flight Service Station, read the form aloud item by item. Be aware that traffic saturation can delay radio filing; AIM suggests pilots use a dedicated filing service if unable to reach ATC by radio. Always note the time of filing.

4. Confirmation and Activation

After submission, confirm that the plan has been accepted by ATC. For IFR flights, ATC issues a clearance (often by phone, radio, or ATC-assigned frequency) that activates the plan. The clearance should match your filed route and altitude (or specify changes). For VFR flights, the plan is activated only when the pilot calls Flight Service (or Tower) before takeoff.

In practice, operators should verify on CTAF/UNICOM that the VFR plan is open; if departing an uncontrolled field, ask FSS to activate the plan and provide the squawk code. Keep a copy of the filed plan and clearance handy in the cockpit. Finally, after landing, ensure the flight plan is closed. VFR/DVFR plans must be canceled or closed with FSS within 30 minutes of arrival. IFR plans to have a towered airport close automatically; if landing at an uncontrolled field, the pilot must cancel with ATC or FSS as soon as possible.

When and Where to Submit a Flight Plan

Timing and destination for filing depend on region and flight rules. In general:

U.S. IFR Flights

File well before departure. The FAA recommends at least 30 minutes prior to ETA for an IFR plan. This lead time allows ATC to process the plan and issue a clearance. (During high-traffic periods or special operations, some operators file even earlier or use ATC Pre-Departure Clearance (PDC) systems.) Submit the plan to an FSS (phone, online, or radio) or via an approved service. If flying VFR in the U.S., file with FSS or tower if you desire flight following; it should be opened by FSS at departure.

Europe/EASA Flights

In Eurocontrol-controlled airspace (Schengen/EU FIRs), the slot/ATFCM rules usually require filing at least 3–4 hours before EOBT (Estimated Off-Block Time). Filing less than 3 hours ahead may flag the flight as a “late filer” and subject it to ATC slot penalties. For example, IFR flights with overflight of ECAC FIRs should be in the system at least 3 hours out, or by midnight if planning a late-night flight.

Plans can be filed via national AIS, Eurocontrol’s IFPS (Integrated Initial Flight Plan Processing System) portal, or approved digital platforms. In Europe, contact the local Aeronautical Information Service (AIS) or Operations Center for filing; some countries also allow filing at the airport via tower or AFIS (Aerodrome Flight Information Service).

DVFR (ADIZ) Flights

Pilots planning to enter an ADIZ (e.g. at the U.S., Canada, or Guam boundaries) must file a DVFR flight plan and receive a discrete transponder code. In the U.S., this is done via FSS before crossing the ADIZ boundary, typically 30+ minutes before penetration. The plan must include planned ADIZ entry point/time and address for defense coordination.

Common Flight Planning Challenges and Solutions

Even thorough planning can be challenged by last-minute changes. Eurocontrol reports that in 2023 reactionary delays averaged 8.2 min per flight, airline-related delays 4.5 min, ATFM flow-management delays 1.9 min, weather delays about 1.2 min, and airport/ATC staffing delays 1.8 min, highlighting how multiple small disruptions accumulate into operational impact. Here are typical scenarios and remedies:

The two charts below show the sources of delays at Core 30 airports by type of delay.

Last-Minute Weather Changes

A business jet filing IFR from Madrid to London finds new SIGMETs for turbulence and thickening clouds along the planned airway at flight time.

- Before departure, update weather briefing and alternates. If conditions have deteriorated, the operator can file an amended route (higher altitude or a detour) or plan extra fuel for holding/diversion. For example, avoid convective cells by rerouting via a more northerly track or switch to an alternate SID/STAR. Always carry sufficient contingency fuel (e.g. +10% or +15 minutes) so you can fly around or go to an alternate airport if the destination weather falls below minima. When airborne, stay in contact with ATC for real-time updates and rerouting if necessary. Professional dispatchers might use weather radar and PIREPs (pilot reports) to adjust the plan enroute.

Permit Delays

A flight to overfly Country X is pending permit approval even as ETD approaches.

- First, ensure you applied for all necessary overflight and landing permits well in advance (check the country’s AIP/RAP or NOTAMs). If a permit is delayed, consider a quick alternate route that avoids the country (if fuel/time allows) and refile your plan. If that’s not feasible, coordinate with your operator’s international flight support to obtain emergency authorizations (e.g. diplomatic clearance or Electronic AIP). In some regions, electronic filing can speed the process. Always have a Plan B destination or route in case a permit is ultimately denied.

Route Denials or NOTAMs

After filing, ATC informs you the requested airway is closed due to a military NOTAM.

- Replan immediately. Identify an alternate published route or direct GPS fixes around the restriction. Use available high-altitude direct routes or Victor airways if below FL180. You may need to adjust cruising altitude for the new path. File an amended flight plan or get ATC clearance in flight for the new route. Likewise, always check NOTAMs before flight; a closed VOR or airway change should be caught pre-departure. For example, if your filed SID is NOTAM’d out, switch to a Standard Departure from a parallel runway. Having flexible ETOPS-capable alternates (if overwater) also helps when enroute changes occur.

ATC Slot and Ground Delays

On a heavily regulated day (e.g. European peak summer traffic), ATC issues a 45‑minute ground delay program, pushing your slot to 30 minutes after your planned departure.

- Adjust your ETD to match the ATC slot. If already airborne, cooperate with ATC vectors and speed adjustments. Before flight, monitor the flow programs (via FAA CDM or EUROCONTROL slot coordinators) and be ready to file updated EOBT (estimated off-block time). Some FMS systems allow for slot management; otherwise, coordinate with company ops to confirm the new departure time with ground handling. If the delay is excessive, consider asking ATC for an alternate routing that might have less traffic. Keep extra fuel aboard if ground holds exceed expected pushback delays.

FAQs

- How do I file a flight plan if I’m flying both VFR and IFR segments?

When a flight includes both VFR and IFR segments, a composite flight plan is used. For example, you might file a VFR flight plan for the initial portion of your flight and then switch to an IFR flight plan as you enter controlled airspace or if weather conditions deteriorate. This requires coordination with ATC to ensure a smooth transition between flight rules, these are start with:

- Filing the Plan: Pilots must file two separate flight plans for the VFR and IFR portions of their flight. The VFR flight plan is typically filed with a Flight Service Station or equivalent flight plan filing service, while the IFR flight plan is filed with Air Traffic Control (ATC).

- Specifying Transition Points: In the flight plan, pilots need to specify the point or points where the change from VFR to IFR rules (or vice versa) is planned.

- Coordination with ATC: The IFR portion of the plan will be routed to ATC, and the VFR portion will be routed to a Flight Service for Search and Rescue services. It’s essential to coordinate with ATC to ensure a smooth transition between flight rules.

- Activation and Closure: Pilots need to activate and close their VFR portion and obtain a clearance for the IFR portion.

- Timing: The VFR flight plan proposals are normally retained for two hours following the proposed time of departure unless the actual departure time or a revised proposed departure time is received.

- Is it necessary to file a flight plan for every flight?

Filing a flight plan is mandatory in various countries, especially for international flights and flights that require crossing borders. Here are some instances where a flight plan is mandatory:

- United States: For all IFR flights, Defense VFR flights in the ADIZ (Air Defense Identification Zone), and certain TFRs (Temporary Flight Restrictions).

- International Flights: The international flight plan format (FAA Form 7233-4) is mandatory for any flight that will depart U.S. domestic airspace.

- Canada: Pilots must file and activate a flight plan for all flights crossing the U.S.–Canada border, including flights with no landing (FAR 91.707).

- China: Flight plans are required for all flights, and there are specific altitude level restrictions and approved airways that must be used.

- EUROCONTROL Network Manager (NM): For every flight in European skies, pilots intending to depart from, arrive at, or fly over one of the countries part of the operational area of the NM must submit a flight plan to the operations center (NMOC).

It’s important to note that these are just examples, and requirements can vary depending on the airspace and the country. Just Aviation is advised to consult the aviation authorities of the respective countries or regions they plan to fly in for the most accurate and up-to-date information.

- What happens if I need to change my flight plan after filing?

If you need to change your flight plan after filing, you must notify ATC or the nearest Flight Service Station as soon as possible. It’s crucial to communicate any changes, such as encountering unexpected weather or needing to divert, to ensure that your flight plan reflects your new route or destination. Additionally, if you have an overflight permit, especially when utilizing a border overflight exemption, you must update the remarks section of your ICAO flight plan accordingly. Remember to promptly report any changes to aircraft, pilots, or crewmembers to Customs, and update the APIS manifest with any alterations to ensure compliance with permit requirements.

- What is the difference between IFR and VFR flight plans?

IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) flight plans are required when flying in conditions where pilots cannot rely solely on visual cues and must use instrument navigation. For example, an IFR flight plan includes specific waypoints, altitudes, and air traffic control (ATC) clearances. VFR (Visual Flight Rules) flight plans are used when pilots can navigate visually; they are recommended for safety but not always required, such as when flying cross-country in clear weather.

Flight planning for business jets is a meticulous process that underpins safety and compliance. It integrates weather, aerodynamics, regulations, and international procedures. Just Aviation plays a valuable role in handling this complexity: we maintain current aeronautical data, obtain permits, monitor SNOWTAM/NOTAMs and weather, and coordinate slot bookings.

By using expert planners and technology tools (while following the steps above) operators can ensure that every flight plan is thorough, compliant with ICAO/FAA/EASA rules, and optimized for the best possible outcome without compromising safety. The end result is a clear, approved flight plan that keeps the crew and passengers safe and keeps regulators satisfied.